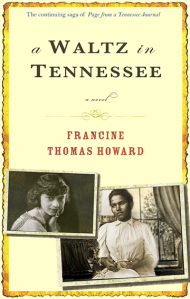

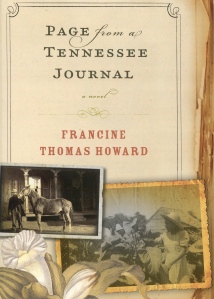

No, I’ve never lived in the South, and yes, I know I’m treading into dangerous waters. But as an author of novels with racial themes–Page from a Tennessee Journal, Paris Noire, and my upcoming A Waltz in Tennessee, I’m compelled to say a few words about the events in Charleston. First, my thoughts and prayers to all those in Charleston. I, too, am an A.M.E. The opportunity to follow the TV coverage of the Mother Emanuel church service was surreal. Though three thousand miles away, I knew the order of service and chimed right in during the call and response readings.

Should the Confederate flag flying over State Houses, et al, stay or go? I refuse to do a knee-jerk reaction. Let’s just look at the facts. The flag defenders, including representatives of the Sons of the Confederacy along with some plain-folk, and presumably, good-hearted white South Carolinians state that the flag does not represent hatred of any one race, but instead, honors the valor of fallen Confederate soldiers. They nail home their point by claiming, rightfully, the stars and bars are a part of South Carolina’s history.

And they are absolutely right. The battle flag of Virginia (the technical background of the stars and bars) does, indeed, reflect the history of not only South Carolina, but of all the states involved in rebellion against the lawfully elected government of their country–the United States of America. Those in rebellion from 1861-1865 lost their bid to overthrow their legally elected representatives. In my college Civics 101 class back in the stone age, the losing side in a Civil War were called traitors. The flags of traitors were not displayed in places of honor, but retired in disgrace. But what of valor, you say?

I don’t doubt the majority of the poor white, almost landless, white men who made up the bulk of the grunts who actually carried the battle forward in Antietam and Gettysburg fought with “valor.” But for what was that valor? Crawling through mud, eating rotten food, wearing rags, shooting at Yankees–courageous, perhaps–but what was it for? At its core, that “valor” aimed at keeping my great, great, great grandmother in the bed of her white owner even though she didn’t want to be there. That “valor” fought to keep my great, great, great Uncle Thaddeus working in a cotton field from sun-up to sun-down with nothing of his own to show for it other than a whip if he protested. This is the “valor’ with which the Confederate soldier fought.

Yes, the Confederate flag represents history–a southern legacy if you will. But it is an ugly history. Much like the 1930s symbol of German power, the swastika, the stars and bars are a legacy best displayed in a museum, not on any State or federally owned property.

I understand many white South Carolinians hold that flag dear. In memory of your own great, great, great, Uncle Billy Bob, I ask you to take it down as a favor. Ask yourselves, does you pride in Uncle Billy Bob outweigh the pain of my Uncle Thaddeus. Do the right thing.